|

James Hamilton, M. D.

THE HEART OF THE MATTER

As I mentioned in Post #6732, the other cardiac problem I wanted to discuss is Atrial Fibrillation (AF), the most common dysrhythmia.

In addition to aging there are several risk factors that predispose a person to experience AF. These include genetics, obesity, excess alcohol, valvular and other structural heart disorders, heart surgery, coronary artery disease, hyperthyroidism, diabetes, endurance athletics and some others.

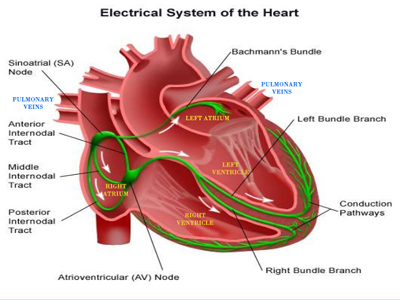

In order to understand AF one must first have some basic knowledge of the normal heart's electrical system (I can just hear the excitement of any of our class electrical engineers!). These two illustrations will help as I briefly go through this.

By means of a complex chemical-electrical process (involving sodium, potassium and calcium ions) starting with something called diastolic depolarization, an impulse is generated (normally about 60-100 times per minute - the normal resting heart rate) in the Sino-Atrial Node and sent via a series of specialized bundles through the atria (causing atrial contraction) of the heart to the Atrio-Ventricular Node which slows the signal (allowing the atria to contract before the ventricles), and then through the bundle branches to the conduction pathways ("Perkinjie Fibers") which stimulate the ventricular muscle fibers to contract. This electrical system is in green on the picture.

Although all of the exact electrical phenomena that occurs in AF are still being investigated, it seems that there are several mechanisms that can precipitate it. Most AF develops just outside the top of the Left Atrium (LA) in the four Pulmonary Veins where they enter the LA.

When the atria fibrillate there is no good pumping action of blood from them to the Right and Left Ventricles (RV, LV). Fortunately the majority of blood that enters the two atria passively flows through the valves between the atria and ventricles (Tricuspid on the R and Mitral on the L). When in a normal state (Normal Sinus Rhythm) the contraction of the atria contributes about 20% to the total volume of each ventricle, In AF, therefore, the ventricles receive and pump out about 20% less of their normal volume with each contraction. As I described in in Post #6732 if you have a normal heart with an ejection fraction (EF) of 70% and go into AF, your EF will decrease to 80% of that 70% and be 56%, still within normal limits of an EF. However, if your EF at baseline is in the low normal range, say 50%, a 20% reduction will take you down to 80% of 50% = 40% which is close to heart failure levels.

The signals that AF send out are very frequent, maybe up to 600 per minute. Not all of those are able to pass through the AV node but, at least in the early stages of AF, the ventricular rate is very fast, perhaps even up to >200, and very irregular ("irregularly irregular" is a term used to describe AF).

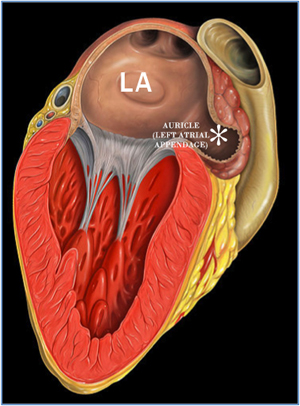

Atrial Fib can come in a number of varieties ranging from acute and short duration, to recurrent to persistent and chronic. Some of the blood that is in the atria is not flowing well and tends to become static, similar to an eddy current in a creek, often in the Left Atrial Appendage (or Auricle -see second illustration). Blood that is static tends to clot and those clots are at risk of becoming dislodged, enter the LV and get pumped out the aorta and on to the brain (stroke), gut (ischemic bowel) or extremities like the legs (ischemic extremities).

The clot formation takes time and is is generally thought to occur if AF has gone on for 48 hours or more. Of course, this is a generalization and other factors can alter that. In acute AF, like during a heart attack (myocardial infarction, MI) if the patient is decompensating rapidly ("coding"), electrical cardioversion may quickly restore normal rhythm. If a patient is not immediately in danger and has been in AF for less than 48 hours, cardioversion may also be a possibility. Sometimes special types of echocardiograms - such as transesophageal echos (looks at the backside of the heart where the auricle is) - can determine if a clot is present before cardioversion.

There are many ways to treat AF. Cardioversion is one, catheter ablation of those initiating foci in the Pulmonary Veins is another way to terminate the AF itself. Medications can also be used to convert the abnormal rhythm. Decisions should be shared by the patient and the doctors involved. Is it possible to restore and maintain normal sinus rhythm or is it to the point where that is not realistic and controlling the ventricular (pulse) rate to a good level along with anticoagulation to prevent clots is the best choice? There are medicines that are designed to control rates, such as beta-blockers, and others that can attempt to terminate the AF. The longer the patient is in AF, the less likely it is that medication will restore sinus rhythm.

The current thinking is that most patients with AF should probably be on anticoagulation. Again, that is between the doctors and the patient and based on various risk assessment tables. There are now available devices, the FDA approved one being the Watchman Device, that blocks the auricle and prevents clots from forming. These may end the need for some chronic AF patients from having to take lifelong anticoagulants.

O.K., believe it or not, this has barely scratched the surface of the topic of AF. But, I hope it has presented an understanding of the problem, what it is and some of the treatments.

Jim

|